Active inference is a scientific field that started as an aligning of neuroscience with the science and maths of physics and probability theory. It was developed by Prof Karl Friston (whose research is referenced the most out of any living neuroscientist). Don’t let the header image (showing the basic formulations of active inference) scare you. We can ignore much of the complexity and look at its quite simple basic premises:

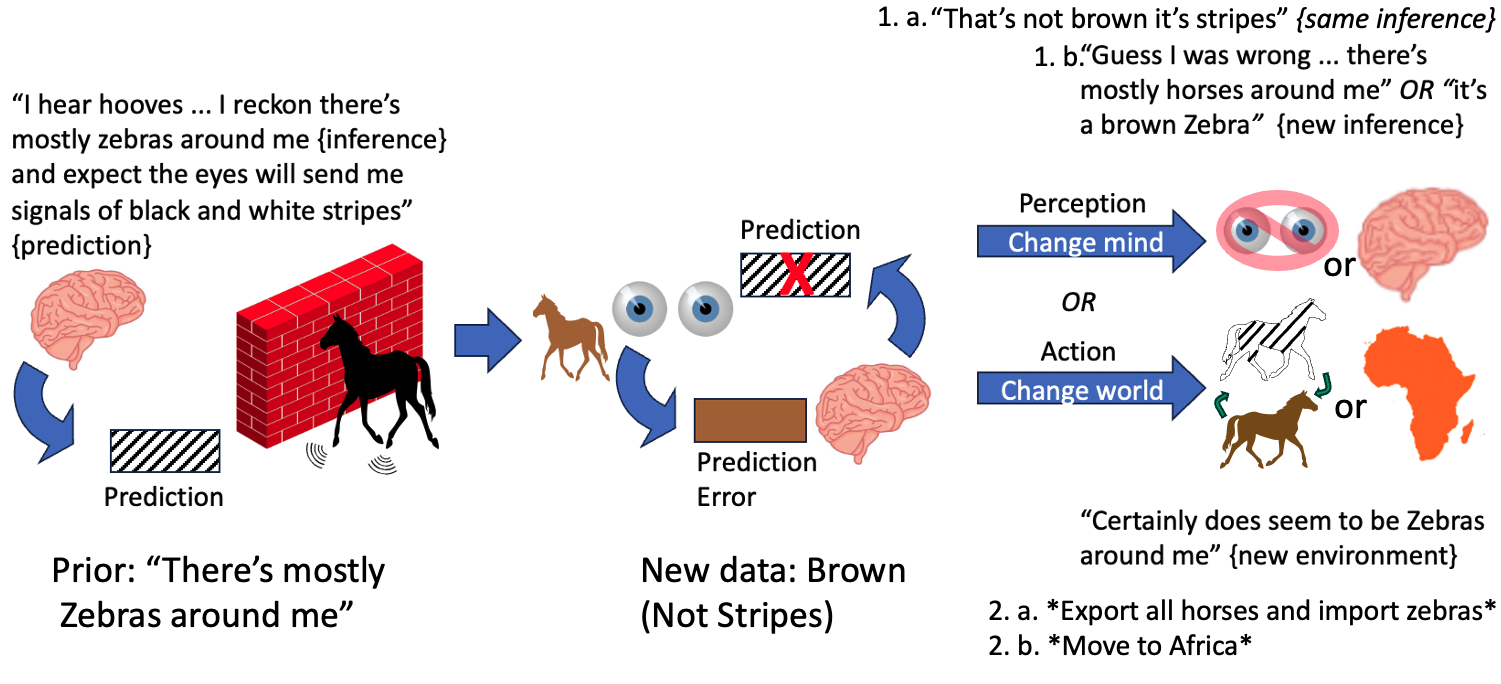

1.) the purpose of the brain is to try to i.) develop and ii.) maintain a helpful fit to its surrounding world

2.) the brain finds its fit through i.) inferring what goes on (and will go on) in its surrounding world, which requires ii.) making predictions of what sensory information it will get from that world

3.) the brain makes its predictions more likely to be accurate by i.) changing its predictions to fit what it gets from the world, or ignoring what it gets when it mismatches predictions, or ii.) taking action to change the world to fit its predictions of what it expects to get

Essentially, to try and stay accurate we can:

i. a.) change our mind (to fit what our senses tell us)

i. b.) pay no mind (to what our senses tell us)

ii. a.) change the world by acting on it (i.e., direct change; e.g., moving something)

ii. b.) change the world by acting in it (i.e., indirect change; e.g. moving ourself, closing our eyes, focusing elsewhere etc.)

In a bit more detail: survival requires fitting into the world (hence, survival of the fit-[t]est)’. Maintaining our ‘fit’ to our world gives the brain a catch-22: avoid change unless it avoids (more) change. That is, our brain tries to keep our ‘fit’ to the world and minimise ‘re-fits’ to it. Re-fitting costs energy and (as far as our brain is concerned), if we are alive, we are surviving, and if we are surviving we pretty much have a ‘good-enough’ fit. Therefore, it will only ‘re-fit’ if that means less re-fitting in the long-term. Unfortunately, knowing how ‘good’ our current fit is and how much better/worse a possible re-fit can be is (and can only ever be) ‘guess-work’ (inferred) for our brain. Our brains will at times act to change what it is getting from its world to make guesses more accurate (and save re-fitting).

You might not be clear on what this really means so far(that is, have a good fit of understanding to what I’m trying to communicate). If so, you can take action and continue reading. Starting with an analogy from an old fable…

The Emperor’s New Tailor

Many have heard the tale of ‘the emperor’s new clothes’… An emperor is tricked into believing clothes that aren’t real actually are, but will be invisible to anyone who is stupid. The emperor and most people around him go along to the belief that he is wearing clothes until a child speaks up of seeing him wearing nothing. The emperor is then laughed at and (depending on the telling of the story) embarrassed at being tricked and publicly unclothed.

Imagine this follow-up to the story: the emperor makes one of his servants his new tailor but is so angry towards all tailors because of the embarrassment of his situation that he refuses to ever see or be seen by one again. In fact, he refuses to ever be measured again and demands that all future clothing is given to him already made (he also refuses to be seen trying them on). Even more, he keeps this tailor locked in the castle so that they cannot speak to other members of the kingdom.

This new tailor unfortunately then cannot directly measure the emperor and has to figure out the right ‘fit’ through guess-work, only receiving feedback from the emperor’s other servants of how ‘pleased’ or ‘displeased’ the emperor seems (depending how good or bad the ‘fit’ is). A difficult task for the tailor as it is not just sizes the the emperor wants a good fit for – the tailor must also guess the kinds of colours and patterns and fabric types that fit the emperor’s preferences (which can change depending on the fashion trends and seasons in the kingdom; something the tailor also does not know due to being locked away). Even more challenging is that the emperor insists on using expensive fabric but also gets angry at the money spent on using this fabric, so when he believes too much is wasted is again displeased.

A difficult task… The tailor learns that the emperor is displeased. Do the clothes not fit well this morning? Has the emperor gained weight (refit needed), or just had a very large breakfast (refit not needed)? Or is there a new trend of colour or fabric that the emperor is now wanting? A difficult task indeed, a task of inference.

The job of the emperor’s new tailor is essentially the same one of our brain. Our brains are trying to find the right fit to their environment (like the emperor). Our brains cannot directly measure the world however, because they are locked away in our skull! They get feedback instead from other organs and nerves (like the servants) such as eyes, ears, and skin (but also stomach, lungs etc.) about this fit and how it is going. Again, finding a fit is a task of inference (never truly knowing what fits the emperor). Updating a fit costs energy (like expensive fabric). So, our brains (like the tailor) have a dilemma: figure out a fit through trial and error of re-fitting, but minimise re-fits as much as possible. Essentially, balance the risk of mis-fitting against that of wasting resources (i.e., try to be as both as accurate and efficient as possible).

Unlike the tailor, what our brains have to infer and create a fit for (the world they live in) is much more complex and changeable! This is especially the case for our human brains because it is the social environment that it is most important to find a fit for.

Actively Tailoring The Fit – Agency

The situation of the tailor and our brain described above is mostly about prediction or inference (i.e., guessing what a good fit is). What is especially important in active inference however, is recognising that we have some ability to act and create change in what a ‘good’ fit actually is. The first and most obvious course of action: to keep going with things as they are when the existing fit seems good(-enough). When the fit seems poor (or about to be poor) however, instead of re-fitting to the emperor/environment, there might be options for the other way around (i.e., to change the environment). The tailor may try to seek out information on current trends. Or perhaps the tailor more directly takes action and encourages other servants to influence the emperor’s preferences by talking aloud “I hear blue diamond patterns on silk are going to be very trendy soon”, “Yes, me too, I wish I could have a robe like that”. Either way, the tailor’s latest design is more likely a fit for the emperor. Of course, taking such actions have their own risk of fit/unfit (it is very unfitting for the emperor to realise when he is tricked or disobeyed).

The ability to act and create change in our environment is called ‘agency’ and is everywhere in life. In fact, quite technically, it is a part of life as we know it. Eating is fulfilling predictions of having nutrients available to our body (similar for breathing and oxygen). Keeping our toothbrush in the bathroom is taking agency that brushing there is convenient (after all, we could keep it in the kitchen or bedroom). Speaking more loudly is taking agency that our words are heard clearly in a noisy situation. Wearing certain clothes of our own (in certain situations) is acting to be seen in a certain way by others (ensuring that their guess of us is a good fit to our own). Building a bypass through a busy traffic area is changing the environment to fit our expectations that a.) there is heavy traffic, but also b.) traffic should move smoothly. Similarly, building muscles through exercise is changing our self to fit our expectations that that a.) there is heavy lifting (of things in the world), but also b.) lifting should move smoothly. Writing several examples of everyday experiences is a way of trying to be understood when describing agency…

Agency and actions aren’t always explicitly observable. If failing a test is unfitting for how I see myself, I can simply not take the test (procrastination can be seen as agency of avoiding expected misfits). Or perhaps in a social situation one person’s facial expressions are closer to my prediction of how people will react to what I’m saying – I can ignore the faces that are unfitting by focusing away (i.e., directing attention) or even by slightly turning my head (i.e., directing field of view). This shows that how we perceive our environment is shaped by how we actively (physically and mentally) orient to it, which is biased to our expectations of what will be perceived. In essence, what we expect and what we get from the world can be quite self-fulfilling.

Self-Tailoring

What our brain is really tailoring to fit our world, is our self. In fact, we can say that our self is a collection of inferences of the world it lives in. Having eyes is an expectation that there is light to see. Having lungs is an expectation that there is air to breathe (or for fish having gills is the expectation that there is water to get oxygen from). Some ‘unfitting’ can be solved through refitting our self/expectations, for example, building muscle in the biceps is refitting for expectation that there is a lot of heavy lifting involved in life (achieved through self-fulfilling action of doing a lot of heavy lifting). Or perhaps a friend says that they’ll meet us at the gym; we arrive at the time we believe they suggested, only to find them not there. We might act by attempting to call them and confirm our belief/expectation is fitting. Or we might instead refit/change our mind (“maybe it was actually tomorrow… they work Mondays”).

A good deal of misfits can only be (or are better) solved through action. For example, our body has an expectation that it will stay roughly within 37°C. Re-fitting our body to 40°C or 34°C isn’t really feasible so instead we tend to act to solve misfit (e.g., changing the environment through air-conditioning or moving to sun or shade, or wearing lighter or heavier clothing). If we get health test results that misfit a belief/expectation “I am healthy”, we can ignore them, but it might be more helpful to refit our belief (“I am unwell”), to then take action (consult a professional) to realign back to “I am healthy”.

These examples show why I like to make a distinction of control and agency: we can’t simply chose to be hotter/colder or more healthy/ill, but we might have some courses of action that can lead to change of those conditions. Perhaps we expect that having a flourishing garden will bring more joy to our life… we can’t control a plant and make it grow, however we can have agency to give it the right conditions for growing.

Agency is widespread in being identified as a feature of mental health. Like anything, healthy agency is about balance and flexibility. For example, a person who (over)controls their feelings, who stops themselves from crying can be considered to be lacking agency (“I can’t feel or be upset” vs “I’m allowed to feel and be upset”). On the other hand, a person who is overwhelmed by their emotions can also be seen to lack agency. My belief is that many severe mental health conditions are where a person has not been able to tailor themselves to their (especially social) environment in a balanced way. That is, they don’t have a strong sense of self, and over-tailor to others or don’t have a strong sense of other’s selves, and over-tailor to their self.

Tailoring Trade-Offs

With the world being as complex as it is, fitting or acting to some part(s) will inevitably be unfitting for some other part(s). From balancing being hungry and being polite whilst waiting in a line for food, to our choice of work or social situations (and indeed work-like balance itself): life is made of trade-offs. Under active inference, we can view most mental health problems as unhelpful trade-offs. Well, from the outside they seem unhelpful, but from the inside things remain a best-guess.

Something key to consider is that active inference is working on all levels of us, right down to our cells. In the grand scheme, most tailoring and trade-offs are impossible for us to be aware of or have psychological agency over (i.e., to “choose and act” in an aware and deliberate way). Feeling anxious when in perceived danger, or pain when harmed, or lousy when ill might feel unpleasant, but are part of important biological-level fits. The psychological discomforts are simply a trade-off to our brain’s best guess of how to survive. We cannot just tell wayward cancerous cells to stop growing or headaches to go away. But we also can’t tell ourselves to “just get over” something distressing. So, to be clear when discussing agency and the power of our predictions in creating our reality – there are certainly limitations to ‘mind over matter’ but also ‘mind over mind’ (and for good reason!).

A clear example of trade-offs is in research that has shown that people (especially those with diagnosable depression) can tend to show preference for information that verifies (prior) negative perspectives about their self over information that can potentially give (new) positive perspectives about their self. Essentially, consistency and predictability show to trump opportunity for a kinder self-perceptive. Staying stuck in negativity avoids having to deal with “risky” refits. Indeed, in my clinical experience many people with severe depression show preference to a ‘stable’ negative world view than a potentially (uncertainly) positive one. Some also stay in harmful social environments. Generally, this staying stuck is due to a lack of experience (and expectation) that any better exists “out there” in the world beyond their world. That is, they infer the world beyond their word as also miserable. It is a life of “better safe than (more) sorry”, so “better the devil[s] you know”. Many might come to “rationally” see the possibility of a more positive self and world, but the negative still feels more real (something however that changes through treatment).

Even at the psychological level, most perception-action and expectation-agency loops operate outside of our awareness. That is, we’re generally mostly unaware how we make sense of and act within our world (again, for good reason as paying too much attention is inefficient use of mental and physical resources). Indeed, the central theme of many evidence based therapies is about building awareness to begin to perceive our own unhelpful fits to then take action of refitting to what is good in our environment or seeking more helpful environments (to which we will hopefully refit). The example of keeping stuck in negative self-views and/or environments is a typical example. Because of how “normal” it seems to be, the negativity of the situations can be quite unknown for the person living it. Again, a person might come to intellectually see a problem but find themselves unable to change. Essentially, they can think of the situation as misfitting, but it still feels more fitting than potential changes. Again, many therapies have a core aim of balancing of what is thought to be to true and what feels true. Unawareness becomes awareness, which becomes ‘knowing’ (thinking about), which becomes believing (feeling to be true), acting, and living a healthier life.

Some Simple Lessons for Living Under Active Inference

- There is no “true” reality for all of us (we all serve a different emperor) but it’s important to share some fit.

Is this ‘the’ real life? Is this just phantasy? It’s probably more of the latter. Under active inference we can say that our experience of the world is created by our brains. There is generally quite a lot of overlap in the worlds that we perceive and experience as individual people. This overlap allows us to talk about ‘reality’ (i.e., ‘the’ real life). However, the fit we must find will always be slightly different to even those most close and similar to us. Regardless, finding overlap and sharing fit with each other is an essential part of mental health. Each of us is a part of the world of the other. As a social species, having some sense of belonging to others (some fit with each other) is crucial to our living and there are few more horrible experiences than having a lack of such belonging and feeling unfitting to the social world. All up, a healthy balance is in keeping awareness that our minds and worlds are not the same but also finding and sharing some similarity.

2. There is technically no “true” fit (there are many ways to clothe an emperor).

“Everyone[‘s brain] is doing their (not ‘the’) best, with what they’ve got. However, everyone[‘s brain] has some agency to get something different in order to be/do something different.”

Consider that some mole rats do not have eyes (no need, their world is mostly dark), or, that the platypus senses electromagnetism (something surrounding us but un-sensed by us). Brings new light (well, not to the mole rats) to the phrase ‘common sense’. In fact, this is very much what evolution shows us: that there are many (more than as many as there are creatures existing) ways to infer (measure) and fit to the world. From bacteria, to fish, to crocodiles, to us. We’re all still around so we’ve found some fit to the same world we share (but by measuring and tailoring to that world differently). The same is true for the social world that we inhabit.

As mentioned, although we can have overlap, we’ll each have a different measure and fit of those around us and people in general. Our perception of every moment is shaped by life up until that moment (and through evolution, the lives of our ancestors). Every choice and action depends on our perception and is loaded with trade-offs that our brain must weigh-up (again, most of them outside of our awareness). Technically, any decision and action our brain makes, is optimal under the situation it perceives itself to be in. Essentially, we can expect no better guesses from anyone’s brain (including our own) given what’s it’s got. However, we do have agency to change what we’ve got and perhaps do a little better at living (with each other). There are rarely “right or wrong” paths of agency to take, just more and less helpful, and different paths can have similar outcomes all the same.

3. Uncertainty is a part of life, so good-enough is good enough (and this is a shifting balance).

Under active inference, efficiency is the aim of the game for our brains. Again, this is where I find it helpful to distinguish control and agency. What is worth investing our time and energy (our life) into changing or maintaining (whether ourself, others, or some other part of the world) is subjective and relative. Many people I work with are tortured by attempts to over-fit with their world: by tendencies of perfectionism, rigidity, over-thinking and planning, trying to get things “just right”; some even try to “hold the world still” and stop it from changing. They have an intolerance to uncertainty, vagueness, and disorder. For them there is no ‘good-enough’, just perfection or failure.

‘The’ world has some natural mess to it and is prone to change (it is what we technically call “stochastic”) however. What fits and is good-enough may well change in a moment. So, it is essential to be able to find a fit (and a self) that is not too tight, that has some flex (indeed, our friend the tailor would have benefitted from elastane). The golden rule (to slightly misquote Einstein) is that “things should be as simple as possible (… but no simpler)”.

4. Our brains themselves are something to have agency with, not control over (both in inferring what’s going on in them and changing what they do).

Some conditions that people suffer from involve a fear that their (sometimes quite horrible and scary) thoughts will become actions because they have already thought them. Some misunderstanding of active inference could worsen these fears. Our minds and brains (like the world they are fitting to) are impossibly complex. We consciously experience only the ‘tip of the iceberg’ and there is inevitably a lot doing its job out of our awareness. I assume everyone relates to phrases such as “What am I doing?” or “What was I thinking?”. Hopefully not too often, but that such uncertainties are normal. ‘Weird’ thoughts are also normal, they are our brains ‘brainstorming’ possible (not highly probable) inferences and actions. Unfortunately, those who take their thoughts too seriously will focus (mentally orient) to more weird thoughts (creating a cycle of reinforcing the importance, focus, and belief of such thoughts).

There is much more that goes between a thought and potential action. Rest assured, our brains will only go with their best guesses of a good-enough fit. Like our environment, our own mind is something that inevitably has some uncertainty to it, something to have agency with, not control over. It is healthy to be curious and reflect on our own minds, but being critical and interrogating them rarely helps. Sometimes not knowing where a certain thought, feeling, urge, or memory came from is ‘normal’. Being able to control which of these do or do not come from our own mind is impossible. Agency towards developing a reasonable (yet flexible) sense of our mind and self is possible (and a goal of most evidence-based therapies).

Summary

Life is all about survival of the fittest. Literally, to survive, we need to find a decent fit with our environment. When we’re unfitting, we can change ourself (to fit our world) or change our world (to fit our self). Staying too unfit leads to death. Changing and refitting too much leads to death. This is the core dilemma, dialectic, and generative process of our brains, minds, and of our very selves.