Trauma quite literally means ‘wound’. It is the ancient Greek word for it, originally referring to physical wounds but now also used to recognise psychological wounds. What qualifies as ‘trauma’ in terms of causes and symptoms is not completely agreed upon. All the same, I find that conditions of the body can be helpful in explaining conditions of the mind, and that trauma is a useful term when doing so. Let’s look at trauma for body and mind…

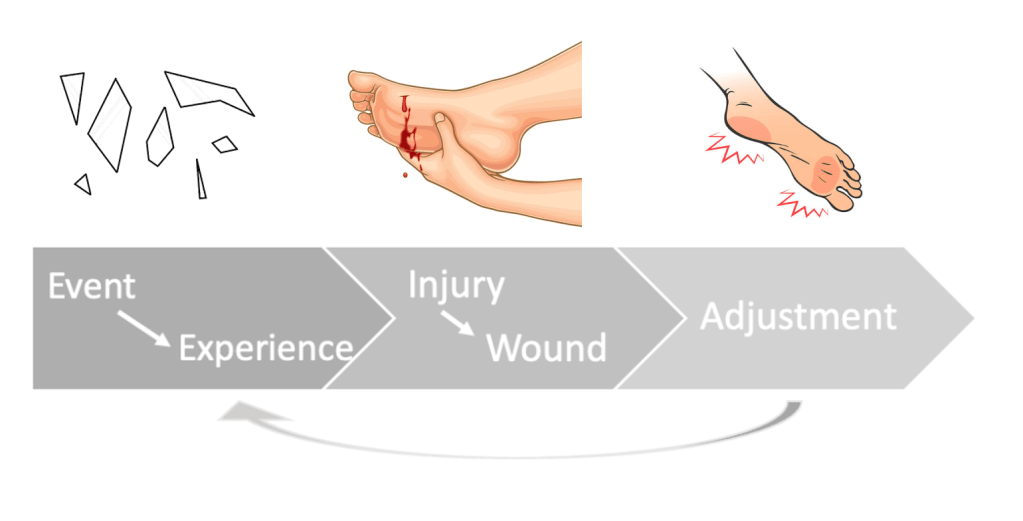

A person is walking along barefoot and steps on a piece of broken glass, resulting in a flesh-wound (a cut). Whilst this wound is unhealed, it can be called a trauma, which the person will likely make some adjustments to (such as limping) to assist recovery and prevent further injury.

Let’s break instances of trauma down with a bit more detail: 1.) something happens (a piece of glass is stepped on) -> 2.) it has an impact (the glass cuts the foot) -> 3.) the impact has impacts of its own (the person limps on the foot). Although this can all be packaged as trauma, I believe it is helpful to make some distinctions between and within these steps.

Event and Experience

“It is personal circumstances and experiences that truly matter in determining how harmful an event actually is.”

It is well shown in research that different people can undergo the same event and have a different experience. This includes events that result in diagnosable trauma conditions for some but not others. Threat and harm are subjective experiences. It is personal circumstances and experiences that truly matter in determining how harmful an event actually is.

Injury and Wound

“… injury [is] the moment of something in the environment impacting a person (e.g., a piece of glass cutting a foot), whilst the wound is the impact (e.g., a cut) … what is actually needing treatment”

We can think of injury as the instance of something in the environment impacting a person (e.g., a piece of glass cutting a foot), whilst the wound is the impact (i.e., a cut: un-intact skin, bleeding etc.) that continues on after that instance. Injury and wound can be interchangeable words. I add the distinction in discussing trauma as I find it helpful to separate the two as what happened and what continues to happen (the latter being what is actually needing treatment).

Adjustment

“… [wounds are] about harm, whilst [adjustments are] about help.”

Adjustment refers to ways in which a person changes something to manage a wound. It is important to separate wounds and adjustments because the former is about harm, whilst the latter is about help. Bleeding and having un-intact skin are the harm of the wound. Pain and limping are adjustments. In terms of psychological trauma conditions, both wounds and adjustments are part of symptoms for diagnostic criteria (e.g., flashbacks of the experience are more a wound, whilst being hypervigilant is more an adjustment).

Adjustments shape our future experiences. Stepping on a smooth pebble usually doesn’t cause harm or hurt, but with an existing cut, it certainly can. Other adjustments like limping and being cautious (even outright avoiding) of areas of possible re-injury are also common and might change our experience in that we step more lightly on the pebble or avoid walking for a few days and prevent the new event all together. This pain, limping, caution, and avoidance might seem problematic but are actually evolved solutions to help in recovery and prevention of further injury. However, this help can become harmful.

Helpful and Harmful Adjustment Trade-Offs

“Our brains do their best with balancing trade-offs, but can’t always do the best.“

Harmful adjustment can and clearly does occur. Limping with a wounded foot is helpful. Limping in a running race with an unwounded foot is not. In fact, ‘pushing through’ an injury and continuing to run an important race might be more helpful than stopping. Even more, some physical adjustments can lead to injuries of other parts of us. Avoiding too much discomfort leaves us more sensitive (e.g., not walking barefoot at all we won’t develop helpful calluses, making us more likely to be injured if caught out without shoes) and deprive the chance for strength development (e.g., using crutches too long can weaken muscle and affect balance). The same is very much true for psychological injury. This is part of the challenge for our brains – trades-offs of when something seems helpful in one way but can be harmful in another. Avoidance can give short-term relief, but also cause long-term problems; it tends to be about ‘how much’ and ‘how long’ that makes something helpful or harmful. Our brains do their best with balancing these trade-offs, but can’t always do the best.

What counts as trauma?

Big ‘T’rauma and little ‘t’rauma

As with physical trauma, trauma conditions traditionally were associated with large and severe events and injuries (e.g., witnessing or experiencing vehicle accidents, physical or sexual assault, military combat etc.). There is growing recognition that experiences of (seemingly) smaller events can indeed be traumatic.

To recognise non-typical trauma, the terms “big T” and “little t” trauma are sometimes used. This can unfortunately be misunderstood that experiences and wounds of little t are not as severe. However, the emphasis is on size of events, not experiences, wounds, and adjustments (again, what actually counts). Before discussing size and scale of injuries and wounds, let’s first consider what it takes for them to improve, to heal and recover.

Healing and Recovery

“Time heals all wounds… Actually, time does nothing, it’s the body (given time and the right resources) that does the healing”.

Modern medical and surgical treatments are truly some of the most impressive advancements of our species. Ultimately, what they generally aim to do however, is assist the body in healing in a helpful way. The majority of injuries and wounds in life need no assistance, the body can sort them out itself. This is given time, but also the right resources to work with. The nutrients and energy from clean air, food, and water are vital for recovery for any wound. When deprived of these resources, healing and recovery can be much more complicated. For psychological well-being, resources for recovery come from relationships (i.e., ‘relational nutrients’): a sense of security, validation, understanding, and care.

Stab-Wounds and Pin-Pricks

Stab-Wounds

Stab-wounds are an analogy for “big T” ‘typical’ trauma events and injuries. They are large and noticeable. Even those not especially educated in health could understand “That must be horrible, I can see how that would impact you”.

Pin-Pricks

Pin-pricks are an analogy for “little t” ‘non-typical’ trauma events and injuries. In fact, on their own they may be seen as instances of difficulty or ‘adversity’ rather than trauma. Adversity, because there is an expectation that they are something unpleasant but that we heal from quite quickly. However, if we are deprived of ‘relational nutrients’, adverse events can leave wounds that do not heal. Perhaps they are as small as a pin-prick. But imagine if most every paper-cut, scrape, and pin-prick you ever had never really healed. That you had to live with each in this very moment. It would be unbearably raw just moving through life and any new injury (however “small”) could be excruciating on top of previous ones. What can be torture too is that there is no single noticeable wound to point to and make sense of the pain… it seems to simply be you.

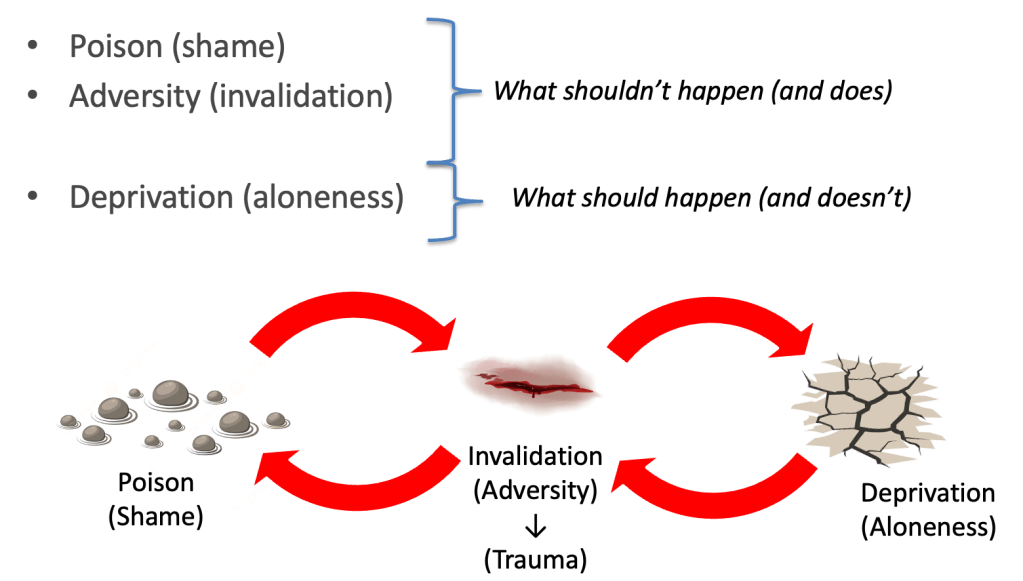

Relational Poison: Social Stings and Toxic Environments

“… ‘relational trauma’… the trauma of being harmfully related to by another … often seems to be more like illness than injury, more poison than wound”

Poison

“… the wounds themselves are not what is severely harmful … rather it is what they let in … not only small but invisible and harms from the inside”

Psychological harm from other people has many names (interpersonal trauma, attachment trauma, developmental trauma), which can come under the umbrella of ‘relational trauma’. That is, the trauma of being harmfully related to by another person (whether they are a stranger or close-one). Relational trauma is a term I use often, though relational harm often seems to be more like illness than injury, more poison than wound.

Poisonous chemicals are those which are harmful to the cell(s) that make up a person. Toxins are poisons created by living things that can harm other living things. In the case of infections, toxins are released by micro-organisms (germs, bacteria), but larger organisms can also release toxins (e.g., through bites or stings). Toxins can also get in and harm us without injuries, through what we eat, drink, and breathe. What is important here, is that the wounds themselves are not what is severely harmful. Rather it is what they let in that truly harms. Something that is not only small but invisible and harms from the inside rather than outside.

Social Stings

Social stings refer to experiences like a moment of feeling judged, alone, criticised, intimidated and such. They come from events of insults, criticism, intimidation, embarrassment, and (even well-intentioned) teasing. If we’re honest, we’ve likely each been a cause of social stings for others at different points in life. Like pin-pricks it is when they do not heal and accumulate that they can become severe.

Toxic Environments

The term ‘toxic’ has become quite commonplace (unfortunately to some extent of being overused) to recognise that social and relational settings can negatively affect our well-being. In this case, it is perhaps not as direct as a moment of being insulted in a social sting. It might instead be a workplace culture, family beliefs, or community prejudice that more generally feels harmful to what is invisible but essentially a part of us (our identity, values, morals, or sense of self).

A toxic environment by itself can of course be a health hazard. However, like a physical wound worsening through infection due to a toxic physical environment, a toxic social environment can lead to psychological wounds worsening rather than healing with time. It goes both ways, the wound lets more poison in and the poison makes it harder for the body to heal the wound.

Harmful Deprivation

“It’s not just about what shouldn’t happen but does, but what should happen and doesn’t”

As mentioned, being deprived of the right resources complicates both physical and psychological healing. Without air, food, and water, things simply break down. Again, relationships are vital for our mind and a crucial source of mental well-being and recovery from adversity and trauma. Paediatrician and psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott recognised deprivation itself as trauma in the above (reworded) quote. Especially as infants and children, not receiving safety from carers can be experienced as danger, not receiving acceptance can be experienced as rejection, and not having a sense of understanding and being understood can be experienced as being alien in an intolerably confusing world. There is a dilemma where it is our core carers who are unable to give care that we need (and are wired to expect). It is a situation like someone with only toxic water available who simply has to find the balance of minimally dehydrating and poisoning themselves.

Auto-Immune and Analgesic Adjustments

Typical trauma generally has a more ‘outside-in’ effect on a person. Threats of physical harm, that there is something wrong “out-there” in the world, becomes the source of stress. Relational poisoning has a more “inside-out” effect. Feelings of shame and guilt become part of a sense that there something is wrong “in-here”. Just being oneself becomes the source of stress.

At extremes some people gain unhelpful adjustments of mistaking normal inside experiences as problems and lose healthy adjustments of being sensitive to abnormal outside threats.

Auto-Immune Adjustment

Auto-immune conditions are where the body’s defences mistake healthy cells as harmful and attack them. People with severe relational poisoning can have something similar going on with their own beliefs, emotions, and very sense of self. They can struggle with feelings of pride, joy, and love even seem to show an ‘allergic’ reaction (allergies are the body mistaking benign external things as harmful) to compliments, care and other relational positives from others.

Analgesic Adjustment

As mentioned earlier, pain is an adjustment and in fact inherently helpful. It can indeed become problematic, but its core purpose is to alert and protect us from sources of harm. There are (thankfully rare) conditions where people are born without the ability to feel physical pain (analgesic conditions). These are severe conditions and many die young due to unnoticed injuries. Whilst hyper-vigilance is a core symptom of trauma conditions, some also show desensitisation to (especially relationally) harmful situations.

Summary

Trauma means wound, and looking at similarities of physical and psychological conditions, it is understandable why they share the same term. This is more straightforward when considering ‘typical’ trauma of “large” scale events. Looking at physical conditions can however teach us that “smaller” does not mean less severe. Many of the most debilitating medical conditions are literally microscopic. The situations in which both physical and psychological injuries occur is crucial as to whether ‘time will heal or harm’ wounds. This includes how much toxicity but also resources there may be in the social environment (relationships, places, community, society).

Grains of Salt

Please keep in mind that the use of bodily trauma to described mental trauma in this article uses analogy. I am unaware of existing scientific evidence that allows us to directly liken these ways of thinking about the two.

Honestly, I do believe that there are some scientific grounds for homology of some aspects of mental and physical trauma. But describing this simply enough to be understandable yet accurately enough to be worthwhile is not something that I have figured out yet.

Read more about analogy and homology and taking ideas cautiously here.